Autonomous vehicles have been described as “almost here” for more than a decade. The technology worked in demos, pilots, and carefully controlled environments, yet widespread deployment remained elusive.

What changes in 2026 is not a single breakthrough, but the convergence of four long-running shifts:

- Electric vehicles becoming software platforms

- Artificial intelligence and AI compute reaching real-world reliability

- Economics crossing a decisive cost-per-mile threshold

- Regulatory frameworks moving from experimentation to deployment

When these curves intersect, adoption no longer moves linearly. It accelerates. 2026 is the year autonomous driving shifts from technological promise to economic and societal reality.

A transition years in the making

Autonomy is often framed as a sudden leap forward. In reality, it is the product of more than fifteen years of sustained research and development.

- Waymo began work on self-driving technology inside Google in 2009, optimising for safety and reliability within defined operational domains.

- Tesla pursued a contrasting strategy, deploying autonomy incrementally to customer vehicles and gathering real-world data at global scale.

These approaches, geofenced precision versus general-purpose learning, evolved in parallel. By the mid-2020s, both reached a point where autonomy was no longer confined to pilots, but capable of operating in open and unpredictable environments.

Why autonomy needed electric vehicles first

A crucial and often underappreciated reality is that true autonomy depends on electric vehicles.

Battery-electric vehicles transform cars from mechanical systems into electronically defined platforms. They enable drive-by-wire steering, braking, and acceleration, centralised compute architectures, continuous over-the-air updates, and deep integration of sensors and AI inference.

Internal combustion vehicles were never designed for this. Autonomy can be retrofitted onto ICE platforms, but it is inefficient, fragile, and costly. Electric vehicles are software-native machines, which makes them the natural host for autonomy.

This is why the most capable autonomous systems have emerged first on electric vehicles, and why autonomy and electrification are inseparable trends.

The AI convergence: autonomy as real-world intelligence

Autonomous driving is not just enabled by AI. It is one of the hardest real-world tests of artificial intelligence ever attempted.

Unlike text or image generation, driving requires AI to perceive the physical world continuously, predict human behaviour under uncertainty, plan and act in real time, and operate safely in adversarial conditions.

If AI can reliably drive a car, it can operate in almost any physical system.

Data meets compute

Two changes in the mid-2020s proved decisive.

First, data scale. Tesla vehicles alone generate billions of miles of real-world driving data per year, creating one of the largest perception datasets ever assembled.

Second, compute scale. Advances in AI chips, from data-centre GPUs to in-vehicle inference silicon, dramatically reduced the cost and latency of large neural networks.

This convergence enabled end-to-end neural networks to replace hand-engineered stacks, faster training cycles, and real-time inference inside vehicles. Autonomy became viable not because of a single algorithmic breakthrough, but because AI compute finally caught up with real-world complexity.

From assisted driving to general autonomy

By the mid-2020s, advanced driver assistance had become common across many vehicles. What distinguished Tesla’s approach was scope rather than individual features.

Its systems operate on city streets as well as highways, handle complex junctions and unprotected turns, and rely on a single neural-network stack across regions.

In December 2025, Tesla reported that a customer vehicle completed a West-to-East coast US journey without human intervention, aside from regulatory supervision. Symbolism aside, the significance was deeper.

Autonomy was no longer confined to routes. It was operating at continental scale.

That milestone matters for insurers, regulators, and fleet economics far more than for marketing.

The economic inflection point and who benefits

The true breakthrough of autonomy is economic rather than technological.

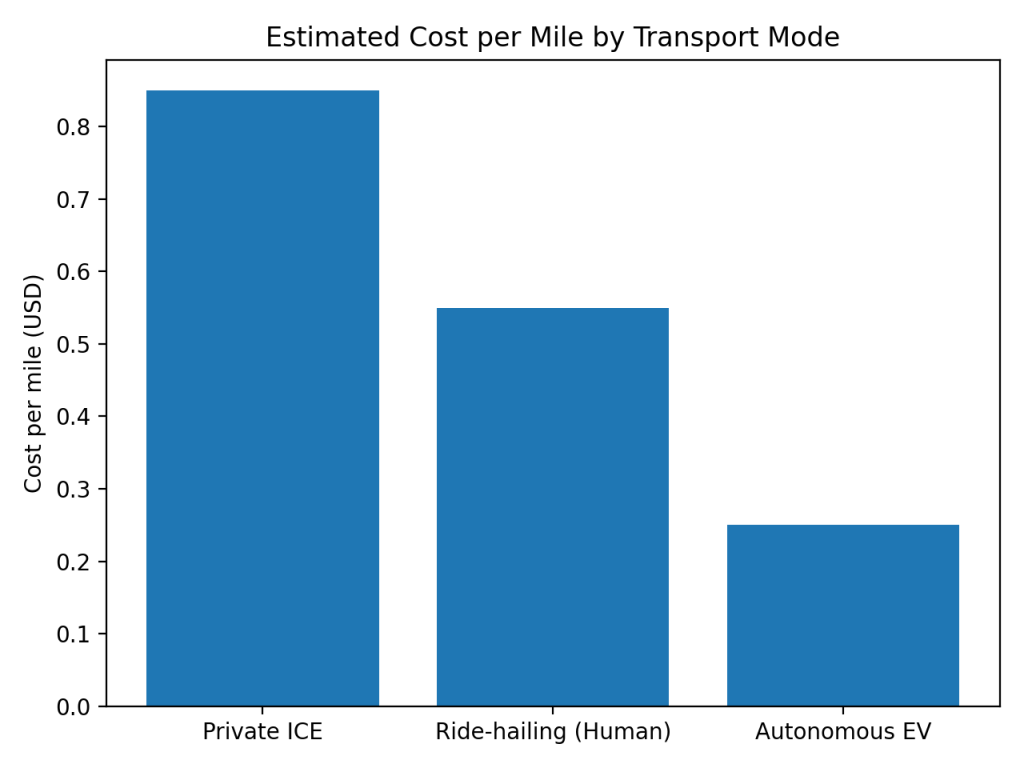

Figure 1: Estimated cost per mile by transport mode

According to analysis from ARK Invest, private ICE vehicles cost roughly $0.70 to $1.00 per mile. Human-driven ride-hailing lowers ownership inefficiencies but remains constrained by labour costs. Fully autonomous electric vehicles could operate at $0.20 to $0.30 per mile at scale.

This is a structural reset of transport economics, and its benefits extend across society.

Households

Transport is typically the second-largest household expense after housing. Lower cost per mile allows many families to avoid owning a second car, replace ownership with pay-per-use mobility, and free thousands per year from depreciation, insurance, and fuel costs.

The largest proportional gains accrue to lower- and middle-income households, for whom car ownership is most financially burdensome.

Older adults and people with disabilities

Autonomous mobility restores independence without requiring driving ability, family assistance, or fixed public transport schedules. Access to healthcare, work, and social connection improves, reducing isolation and informal care burdens.

Cities

High-utilisation autonomous fleets allow cities to operate with fewer total vehicles, reduce parking demand, lower congestion and pollution, and reclaim land for housing and green space. Mobility becomes a managed service rather than a parking problem.

Workers

While driving jobs will change, cheaper transport expands labour markets. Longer commutes become affordable, job access widens, and participation barriers fall for carers and part-time workers. The effect is not simple displacement, but greater labour-market fluidity.

Governments

Autonomous fleets improve access without permanent subsidy. They reduce accident costs, infrastructure strain, and demand for inefficient transport routes. Once deployed, they function as self-financing infrastructure.

Utilisation: the hidden accelerator

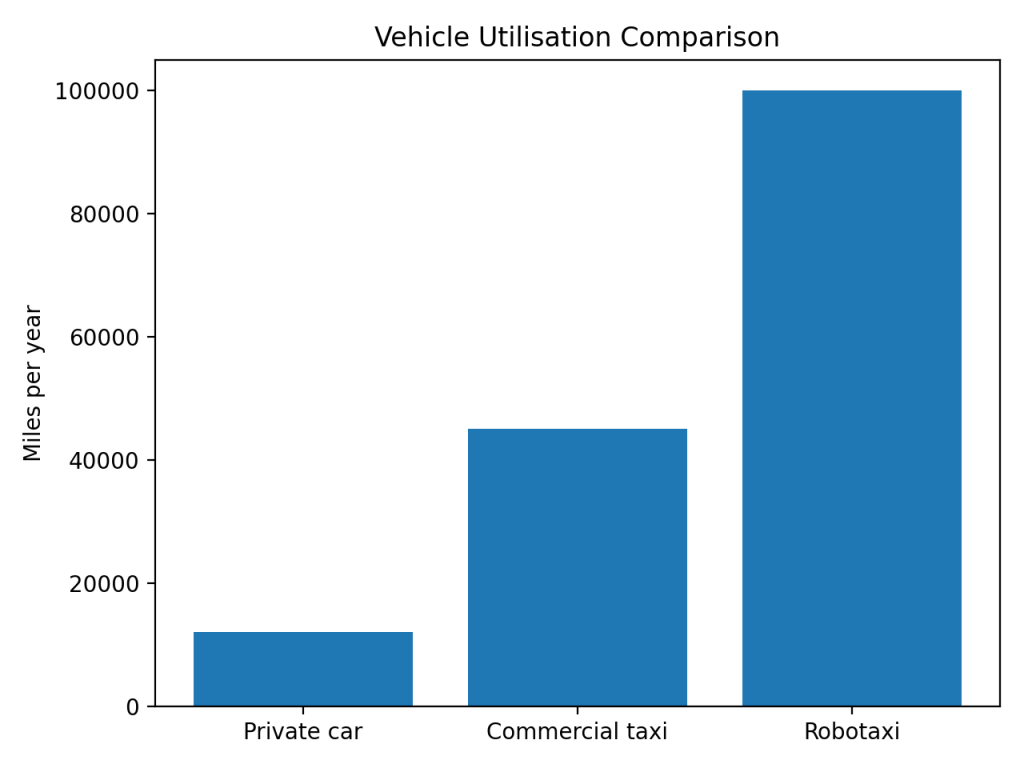

Figure 2: Vehicle utilisation comparison

Private cars average around 12,000 miles per year. Robotaxis could exceed 100,000 miles annually, spreading fixed costs, accelerating learning, and improving service availability. This utilisation flywheel underpins both the economics and the pace of improvement.

Regulation is catching up

Regulatory progress is often underestimated. The United States has enabled city-level deployment, China has accelerated large-scale pilots, and the EU and UK are moving from frameworks to approvals.

In early 2026, Tesla is expected to advance regulatory processes via the Netherlands, a key EU homologation route. What matters is not uniform approval, but predictable momentum.

Autonomy accelerates electrification

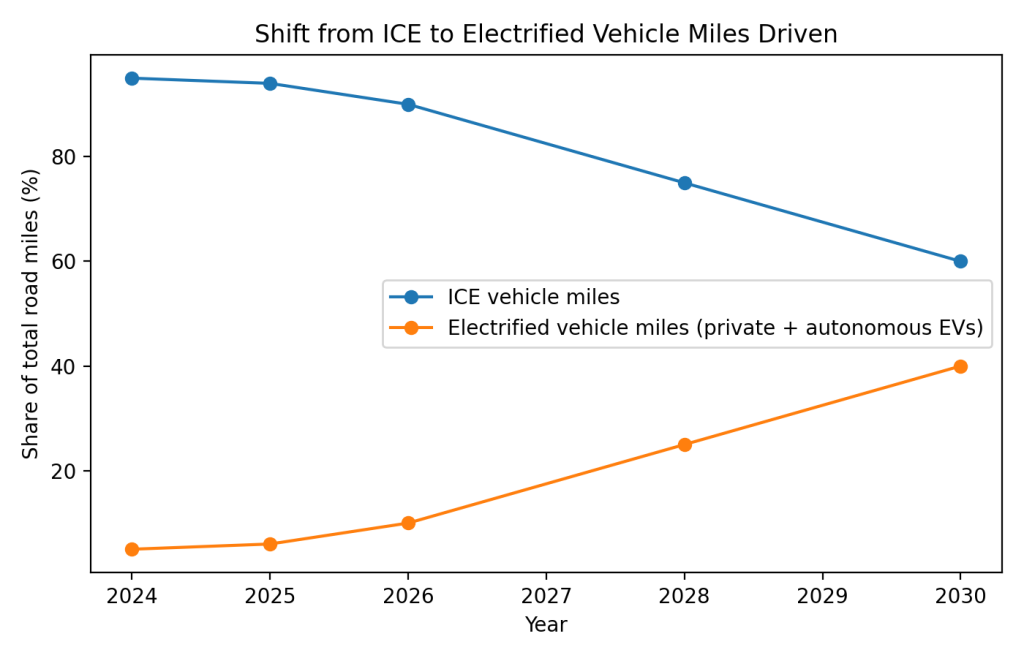

Figure 3: Growth in electric miles driven

Autonomous fleets drive five to ten times more miles per vehicle than private cars. Because autonomy is tightly coupled to electric vehicles, each deployment displaces disproportionately more ICE miles.

This makes autonomy one of the fastest and most effective levers for reducing transport emissions without requiring behaviour change.

Why 2026 is the inflection point

None of these trends are new. What makes 2026 different is synchronisation. Electric vehicles function as software platforms. AI is capable of real-world decision-making. Economics undercut human driving. Regulatory pathways are becoming predictable.

Technology adoption follows S-curves. 2026 is where this curve bends sharply upward.

Autonomous vehicles will not eliminate private car ownership overnight. But once mobility becomes cheaper than ownership, available on demand, safer by default, and electrified by design, the question shifts.

Why would people pay more not to use it?

In 2026, that question starts to becomes unavoidable.

Leave a Reply